At his trial [for treason], Alexander Ulyanov Lenin’s older brother), refused to be represented by counsel and carried out his own defence. In an attempt to save his comrades, he confessed to the acts he had never committed. In his final address to the court, Ulyanov argued: "My purpose was to aid in the liberation of the unhappy Russian people. Under a system which permits no freedom of expression and crushes every attempt to work for their welfare and enlightenment by legal means, the only instrument that remains is the terror. We cannot fight this regime in open battle, because it is too firmly entrenched and commands enormous powers of repression. Therefore, any individual sensitive to injustice, must resort to terror. Terror is our answer to the violence of the state. It is the only way to force a despotic regime to grant political freedom to the people." He stated that he was not afraid to die as "there is no death more honourable than death for the common good" - John Simkin, Spartacus Educational.

As these lines will show terrorism was not the answer, but Lenin at this point was reported as saying "I'll make them pay for this! I swear it." As a tool, instead of terror, he chose Marxism.

As these lines will show terrorism was not the answer, but Lenin at this point was reported as saying "I'll make them pay for this! I swear it." As a tool, instead of terror, he chose Marxism.

This essay is about the man and the circumstances both of which at a different time and in different locations created the opportunities that heralded him into the limelight of power. We shall find out whether the Revolution of October 1917 was already underway and on the last leg in achieving its goal, for the overthrow of Russia’s Tsarist Monarchy, or was it Vladimir Lenin who seized the opportunity at that point and usurped an ongoing revolutionary movement already in progress to assume the leadership?

It is worthwhile to pause at this point to know more about the man. This is how Victor Chernov, Lenin's fellow revolutionary and political rival described him "Lenin's intellect was penetrating but not broad, resourceful but not creative; a past master in estimating any political situation, he would become instantly at home with it; quickly perceive all that was new in it and exhibit great political and practical sagacity in forestalling its immediate political consequences. Lenin was a great man. He was not merely the greatest man in his party; he was its uncrowned king, and deservedly. So he was its head, its will, I should even say he was its heart were it not that both the man and the party implied in themselves heartlessness as a duty. Lenin's intellect was energetic but cold. It was above all an ironic, sarcastic and cynical intellect." Moreover, Lenin was the only Russian politician to regard revolution as his sole purpose in life. A Menshevik called Pavel Axelrod summed Lenin up by describing him as "the only man for whom revolution is the pre-occupation 24 hours a day, who has no thoughts but of revolution, and who even in his sleep dreams of nothing but revolution."

It is worthwhile to pause at this point to know more about the man. This is how Victor Chernov, Lenin's fellow revolutionary and political rival described him "Lenin's intellect was penetrating but not broad, resourceful but not creative; a past master in estimating any political situation, he would become instantly at home with it; quickly perceive all that was new in it and exhibit great political and practical sagacity in forestalling its immediate political consequences. Lenin was a great man. He was not merely the greatest man in his party; he was its uncrowned king, and deservedly. So he was its head, its will, I should even say he was its heart were it not that both the man and the party implied in themselves heartlessness as a duty. Lenin's intellect was energetic but cold. It was above all an ironic, sarcastic and cynical intellect." Moreover, Lenin was the only Russian politician to regard revolution as his sole purpose in life. A Menshevik called Pavel Axelrod summed Lenin up by describing him as "the only man for whom revolution is the pre-occupation 24 hours a day, who has no thoughts but of revolution, and who even in his sleep dreams of nothing but revolution."

The year 1917, was a revolutionary year in Tsarist Russia which saw the Romanov Dynasty coming to an end after three hundred years of rule, at the first revolution in March of that year. The immediate causes of World War I brought in the second, the October Revolution that made way to the Lenin led Bolshevik Communist Party to government, and eventually to a communist dictatorship. Both revolutions were driven by a political power culminating in forcible regime change. The two revolutions however, were parts in a series within a revolutionary period, that had started as early as the 1860’s emancipation of the Serf. It stretched to a time when the peasants who remained in the countryside, as well as those who had filled the squalid, overcrowded and disease-ridden towns and cities of Russia’s industrial growth, during the 1890s, and the immediate pre-war years. This powerful conjunction of events served to strain Russia’s old order beyond breaking point.

The mounting unrest against the war and the ruling regime, had deep-rooted grievances and injustices. On the one hand, the Monarchy perceived threats arising from contradictions between their divine justification due to their outdated Orthodox Church with its steadfast hostilities to western heresies, and the Industrial Western technology. Such contradictions failed the ruling elite, The Bourgeoisie of Russia from reaching out in bringing down the old order that would have helped Russia to share in the limelight of power status on the European stage. At the same time, the Russian people were being pressurised by the monarchy’s autocratic rule. Despite the emancipation in the mid-nineteenth century, there were still numerous social stresses on the vast peasant masses, which remained impoverished, resentful and land-hungry. Such social extremes aggravated the relationship between the peasants and landowners, manifested in the many uprising that began springing up against landlords before the breakup caused of the war.

It was around this time that many of the political parties were formed in rural Russia and later joined by the industrial workers in cities across the country. Factory workers, sailors and soldiers were typically peasants mostly coming from their native villages to live in squalid, overcrowded dormitories. There was a massive concentration of disaffected and alienated subjects were to play a decisive part in the revolutions of 1917.

Such breeding grounds gave rise to the germs of radicalism, socialism, Marxism and forces advocating the eventual overthrow of the Romanov Regime. The communist party that formed within these groupings was, split between the Menshevik (Minority) party and the Bolshevik (Majority) party led by Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, (otherwise known as Lenin) his revolutionary name). Lenin advocated a Marxist political movement fired up by intellectuals of the party, to do the thinking for the masses and the eventual overthrow of the Elite and the Monarchy. Briefly, Bolshevism was an adaptation of Marxism to Russian conditions, for a quick and immediate overthrow of Capitalism. It differed from the Menshevik approach which advocated a process of gradual integration of socialism, into the industrial cities and heartland of Capitalism, to set the stage for the ultimate revolutionary change to Communism.

February and March of 1917 were two crucial months in Russia’s history in many ways. The interacting forces, internal and external, long-term and short-term created fertile ground for political agitation. The anger of the masses was brewing finally coming to a head in February. Declaring war on Germany served only a limited uniting force on the Russian people, but a year into the war cracks started to show. Russia was beginning to experience many defeats on the battlefields, retreat by soldiers and refugees were on the increase; food, and in particular bread, shortages were causing severe social unrest. Whilst, the bulk of the Russian army was committed to war, factories were fully engaged in war production (but without some clear direction), the Russians risked a national catastrophe.

Tsar Nicholas II assumed personal rule much against the advice of his ministers and the weak Duma (Russian parliament), at the Winter Palace, to rule along the lines of a military dictatorship. Notwithstanding the spread of secret police across the country, strikes were on the increase in Petrograd, (previously called St Petersburg and in 1924 named Leningrad but in 1991 back to Saint Petersburg). The flashpoint in February was when troops sided with the crowd and fired at the police. At this point, the army mutiny spread, and the authorities lost control of the city, and the target of people’s anger was the monarchy. The Tsar's hold on power collapsed by default. The presence of a weak government emboldened the rural communities, by now growing more militant started to encroach on the landed gentry privileges and demand land sharing. In the cities, workers were demanding higher wages and shorter working week and the employers were forced to concede on all their demands.

By now the state was collapsing 1917 and Lenin sensing this weakness returned to Petrograd from exile in Switzerland, via Germany, to take the reins of the social revolution, determined to overthrow the present regime and to seize power as outlined in his "April Thesis". He knew full well his supporters were concentrated in the crucial areas of the major cities and within military units of northwest Russia. Soon enough, he had persuaded his fellow members that the Bolshevik party was ready to take power; from that point in July and August membership and support of the party snowballed.

|

| Revolutionary workmen and soldiers robbing a wine-shop (1917) Spartacus-educational.com |

These militant forces were springing up from ordinary working citizens; what Karl Marx, Prussian Philosopher and co-founder of Marxism, had called 'The Proletariat', demanding social justice, joined by sailors and soldiers, whose main issues were peace and to see an end to the war. Formed Soviets (councils) took direct action for seeking self-representation. Polarising was the mainstay for two opposing ideologies; to be present at one time meant disaster is not far off. To counteract the agitation by these committees the government, what was left of its authority, initiated severe repressive steps by rounding up their leaders targeting the Petrograd Soviet. Also, in attempts to bring law and order, it applied Marshall Law on railway and factory workers introducing the death penalties on army deserters. Many of the Bolshevik party members were arrested. Lenin fled to a safe house in Razliv, Finland, where to kill time, he worked on a book " State and Revolution", initiating steps for the Proletariat to overthrow the regime. Government troubles did not subside but only went to show that central authority was cracking up at the pressure.

By October 10th armed uprising was on the agenda which saw the Bolshevik Party’s Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC), converted against policing the city from possible German invasion into an organ for the seizure of power. On a show of strength, on 24th October government troops shut down Bolshevik offices and their printing press and aimed to take back control of the strategic places that the party occupied. At this point defence turned into attack and countermeasures were the order. On the 25th of October, the MRC by persuasion and by force retook those vital strategic offices infiltrated the Winter Palace, and arrested the ministers, 'The Bourgeoisie.' The Social Revolution by the Proletariat was on its way and On 7 November – or 25th October by the Russian calendar, the Bolshevik Party came to power.

On 24th October 1917, Lenin wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already; putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of Soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested; the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for a delay when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything."

Clearly, the war had a massive effect in weakening the state. The anachronistic rule by the Monarchy did much harm to the social fabric; laid grounds for grievances and opened the floodgates of militancy. The resulting direct action, was inevitable especially when there was the need by the people to end the damaging war. For the ruling bourgeoisie, that was not on the agenda since Russia was committed to continuing fighting with its allies, Britain and France; ending the war would also have meant surrendering to Germany. In fact, that is what eventually did happen in 1917 at the Peace Conference at Brest-Litovsk (now Belarus) between Germany and Bolshevik Russia. Although other socialist groups, the central committee were ready to cooperate with the Central authority in drawing up a new constitution, the thirst for Soviet power was on the increase. However, there were no apparent signs for these talks to mean much and the likely hood that they end in a bloodbath, was not far away. The government had consistently failed to deliver on its promises for improving living standards and turned a deaf ear to ending the war.

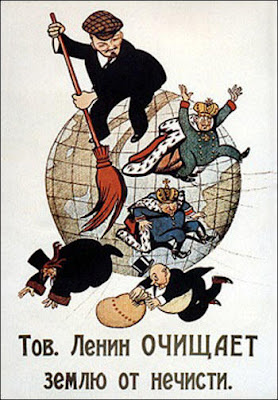

“The Bolsheviks’ success was the work of thousands. It was a matter of hard graft at the grassroots. It was also fostered by creative propaganda – newspapers, speeches and posters – and those were funded handsomely by German gold. The Bolsheviks would always deny this – it would have looked like treason – but when it came to German cash, Lenin had a most original excuse. His ultimate aim, after all, was to "destroy capitalism.”

“All Power to the Soviets” was Lenin’s drive for power. In true demagogue style, he zeroed in on grievances of the masses and weakness of the government in ending the war. He exaggerated the powerlessness of the Bourgeois provisional government led by Kerensky followed by the abdication of the Tsar, and promoted the anti-feelings around it. It is, therefore, no exaggeration to say, by bypassing the Central Committee, the October revolution would not have occurred without Lenin. He also had a knack for good timing; he knew when to push his advantage and when to ease the pressure to act. He began writing ‘The State of Revolution’, while he was in his haystack, calling on the Bolsheviks to destroy the old state machinery, to overthrow the bourgeoisie, destroying parliament, for the revolutionary “Dictatorship of the Proletariat.”

Of Lenin -

‘His sympathies cold and wide as the Arctic Ocean; his hatreds tight as the hangman’s noose; his purpose to save the world; his method to blow it up.’

- Winston Churchill

No comments:

Post a Comment